Air pollution is plaguing the world’s oldest subway system, a new study warns, with high levels of tiny metal particles found in dust samples throughout the London Underground.

Whether these particles actually pose a risk to human health remains an open question, British researchers acknowledge. But experts say it’s happening in subway systems elsewhere, including the United States.

The London Underground, especially, is poorly ventilated, the authors of the new report noted. And the bits of a form of iron oxide in question are often incredibly small, far smaller than a single red blood cell.

So the threat, the study team cautioned, is that easily inhaled metallic particles can readily enter into the bloodstream of the network’s 5 million daily passengers. Prior research has linked that kind of exposure to a higher risk for serious issues such as Alzheimer’s disease and bacterial infections.

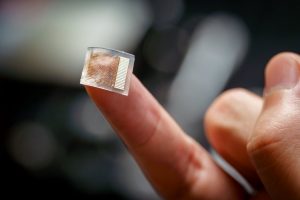

“Our study looks at nanoparticles of iron oxide — particles between 5 nm [nanometers] and 500 nm in size — which are generated by the braking system,” explained study lead author Hassan Sheikh, a risk researcher with the Centre for Risk Studies at the University of Cambridge, in the United Kingdom.

The particulates are byproducts of the routine workings of train brake blocks, collector shoes and motor brushes. They may also be released by the friction caused by the interaction between the metallic wheels of the system’s cars and steel rails.

The end result: Maghemite, a common magnetic mineral that, once formed, is likely repeatedly kicked around the subway environment by rumbling trains, Sheikh said.

It’s the mineral’s magnetic feature that is at the heart of the new analysis, which builds on a number of standard air filter studies that had already demonstrated that general air pollution levels inside the Underground are higher than safe limits established by the World Health Organization.

Those earlier efforts also attributed the Underground’s particulate matter problem to the routine interaction between wheels, tracks and brakes.

But the latest investigation goes a step further, turning to magnetic “fingerprinting” — alongside highly sophisticated microscopes and 3D imaging — to give a much more detailed analysis of 39 Underground dust samples collected in both 2019 and 2021.

Samples were gathered in platforms, ticket halls and cabins manned by train operators throughout the city’s major lines.

In the end, the research team determined that maghemite particles are found “in abundance” throughout the Underground.

Sheikh pointed out that his team’s method appears to be far better than past attempts at painting an accurate picture of the problem. For example, he noted that tiny individual particles sometimes “masquerade as larger particles, because they naturally clump together.”

Traditional pollution analyses, he noted, typically pick up on such clusters, which can be as big as 100 to 2,000 nm in diameter. But they usually fail to catch the tiny — and riskier — particles, which were found to be about 10 nm in diameter, though sometimes as small as 5 nm.

And the concerns raised are not confined to London’s metro, experts warn.

For example, a 2021 study funded by the U.S. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences that cites poor air quality — and tiny inhalable particulate matter, specifically — as a looming concern throughout U.S. public transit systems that every day serve tens of millions of commuters all across the Northeast.

That concern is seconded by Dr. Aaron Bernstein, interim director of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Center for Climate Health and the Global Environment, in Boston.

“Yes, prior studies have found high levels of air pollution in subways,” said Bernstein, “including in New York.”

Still, commuters should not abandon mass transit, he stressed.

“The subways of major cities dramatically reduce road traffic — and associated air pollution — and often have shorter commute times than road-based equivalents,” noted Bernstein. “This research and others point to a need to address the air quality in subways, which is entirely feasible.”

Sheikh agreed.

“At this stage, there is conflicting evidence for whether this specific type of pollution is more or less harmful than the exhaust and non-exhaust-dominated traffic pollution experienced in outdoor environments,” he stressed, adding that more research is needed.

“[But] imagine dragging a simple hand magnet through a pile of iron filings,” Sheikh suggested. “The iron filings are strongly attracted to the magnet and provide an efficient way to collect them. The dominance of magnetic particles in the particulate matter air pollution means that magnetic traps or filters could be used to prevent the particles being emitted in the first place, or to more efficiently clean up dust that has accumulated over time.”

In the meantime, he added, “for commuters, wearing a mask would potentially restrict direct exposure to particles in the Underground.”

Sheikh and his colleagues published their findings online Dec. 15 in the journal Scientific Reports.

More information

There’s more on the health issues raised by fine particulate matter in mass transit systems at the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

SOURCES: Hassan Sheikh, risk researcher, Centre for Risk Studies, University of Cambridge, U.K.; Aaron Bernstein, MD, MPH, interim director, Center for Climate Health and the Global Environment, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston; Scientific Reports, Dec. 15, 2022, online

Copyright © 2024 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

-300x225.jpg)