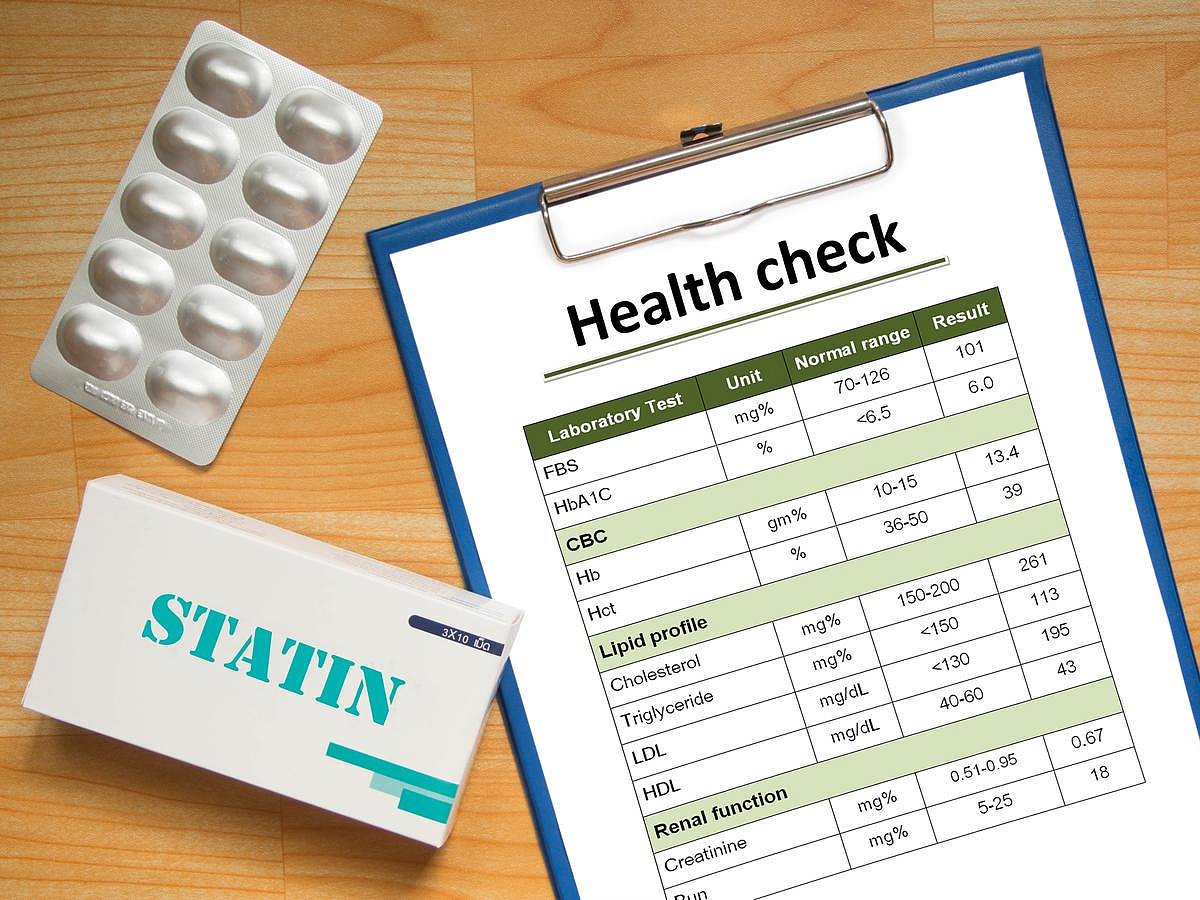

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has delayed the full approval of Novavax’s COVID-19 vaccine. The decision had been expected by April 1, but the agency now says it needs more information before moving forward. The Novavax shot is already available under emergency use. But full FDA approval would allow the vaccine to be used more widely and could offer more reassurance to people looking for options besides the existing mRNA vaccines, CNN reported. The delay dovetails with moves by Republican lawmakers in at least seven states to ban or limit mRNA vaccines. Some, according to KFF Health News, are also pressing regulators to revoke federal approval for mRNA-based COVID shots, which President Donald Trump has touted as a key first- term achievement. Novavax uses protein-based technology, a more traditional method than the mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna. “As of Tuesday, April 1, we had responded to all of the FDA’s information requests and we believe that our [Biologics License Application] is ready for approval,” Novavax said in a statement, adding that its application “included robust Phase 3 clinical trial data that showed our vaccine is safe and effective for the prevention of COVID-19.” “We are confident our well-tolerated vaccine represents an important alternative to mRNA COVID-19 vaccines for the U.S.,” Novavax added. The delay comes as the FDA is undergoing leadership changes.… read on > read on >

.jpg)

-150x150.jpg)